Discovering an author’s body of work can be intimidating, especially for some one as prolific as Connie Willis. Willis, a multiple Nebula and Hugo Award winning author and a SFWA Grand Master, has written over 15 novels and dozens of short stories since the 1980s, with no signs of slowing down. If you’re brand new to Connie Willis, fear not! A.M. Dellamonica is here to guide you through.

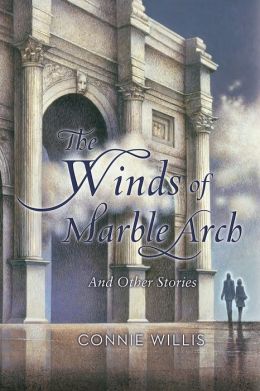

I started this essay by pulling out the compendium of Willis’ short fiction, The Winds of Marble Arch, with an eye to finding “Blued Moon.” My thought was that light, bubbly comedies are how I got started on Connie Willis, and they made a bright, lasting, and pleasant first impression. And hooray—it’s there—so I can recommend that same starting point to you!

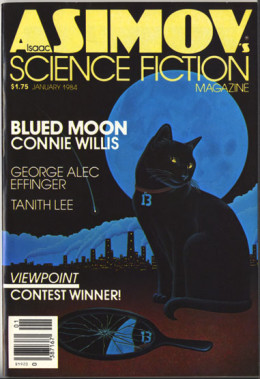

“Blued Moon” appeared in Asimov’s SF in January 1984. By then, its author had been selling SF stories for a half-dozen years, and her work was beginning to appear regularly in the better-known markets of the time. It’s about about linguistics and chaos theory and fads in language generation, with a romantic storyline which serves as the backbone for these ideas. It was nominated for a Hugo Award, just one short year after its author won her first, for “Fire Watch.”

“Blued Moon” appeared in Asimov’s SF in January 1984. By then, its author had been selling SF stories for a half-dozen years, and her work was beginning to appear regularly in the better-known markets of the time. It’s about about linguistics and chaos theory and fads in language generation, with a romantic storyline which serves as the backbone for these ideas. It was nominated for a Hugo Award, just one short year after its author won her first, for “Fire Watch.”

It’s also got at least one truly great pratfall.

If you are somehow coming to Willis with no experience whatsoever, then why not meet her as so many others did in the Eighties, with this zany and carefully constructed romp about humans who are busily and passionately engaged with misunderstanding science, the universe, and each other? (If you love it, and just want to extend the giggly part of the honeymoon indefinitely, don’t hesitate to go find Impossible Things, and “Spice Pogrom,” which is longer and just as delicious.)

I recommend the comedies in part because they are fun, of course, but also because if you don’t know Connie Willis already you might not know that she is a writer with immense artistic ambition. Her heroes include Shakespeare and Heinlein, Mark Twain and Dorothy Parker, Shirley Jackson and Charles Dickens… and one of the things she explicitly pursues as an artist is range. She wants to be nothing less than great both at writing laugh-out-loud comedy and searing, intimate, heartbreaking tragedy.

Imagine meeting somebody who’d got to their thirties and never really dipped into Shakespeare. Who would you recommend? If it was me, I’d never go with Macbeth or Othello. I’d pick As You Like It, or possibly Twelfth Night. I might even go with A Midsummer Night’s Dream, even though it’s not my personal favorite. They’re crowd-pleasing, the comedies. They let you see the author can do brilliant things, and while they’ll probably contain a few disturbing little undercurrents—because the best comedy always grows out of a seed of darkness—they’re not going say hello by ripping your still-beating heart out of your chest and throwing it to the first available pack of wolves.

Imagine meeting somebody who’d got to their thirties and never really dipped into Shakespeare. Who would you recommend? If it was me, I’d never go with Macbeth or Othello. I’d pick As You Like It, or possibly Twelfth Night. I might even go with A Midsummer Night’s Dream, even though it’s not my personal favorite. They’re crowd-pleasing, the comedies. They let you see the author can do brilliant things, and while they’ll probably contain a few disturbing little undercurrents—because the best comedy always grows out of a seed of darkness—they’re not going say hello by ripping your still-beating heart out of your chest and throwing it to the first available pack of wolves.

This brings up another thing, because it’s tempting to hear this as “Start with the easy stuff.”

On the contrary, I would argue that tragedy and carnage are easy to pull off, at least when compared to successful humor writing. Humor is, in fact, devilishly hard. Imagine a world where TV’s Game of Thrones was required by law or ridiculous circumstance to have one episode or storyline—one full hour of television per season out of the ten they give us—that was an unmitigated laugh riot. Would you want to be the one tasked with writing it, or would you rather beat up Theon some more?

So: comedy. It’s an icebreaker, an opportunity to show off, and—finally hewing back to the point—few SF writers do it better than Willis. So start with “Blued Moon.” You won’t be sorry.

So: comedy. It’s an icebreaker, an opportunity to show off, and—finally hewing back to the point—few SF writers do it better than Willis. So start with “Blued Moon.” You won’t be sorry.

What about moving on to the darker stuff?

That first Hugo and Nebula Award winner, “Fire Watch,” is where I’d go next. It is the beginning of the Oxford time travel sequence, a universe where Willis spends considerable time and energy, and it is about loss, mortality and, once again, misunderstandings. This is a theme you’ll see again and again in these works: Willis is very much about humans not only making the wrong assumption, but taking it to illogical extremes.

“Fire Watch” is the diary of a young historian who’s headed out on a field trip, an important core requirement for his degree. His mission: time travel to the past and observe the locals (or contemps, as they’re called). A clerical error sends him to the London Blitz, where he’s assigned to the fire watch for Saint Paul’s Cathedral. It’s not his chosen historical period; he was looking to hang out with Saint Paul. He’s unprepared and has no idea what’s going on, and in a rush he uses advanced learning technology to dump a bunch of facts about the 20th century into his long-term memory, hoping they might surface at a point where they can save him from being arrested for a traitor, or blown up by a German incendiary.

I’ve heard Willis say more than once that time travel is an inherently sad genre, because the traveler moves through a world that is already gone. Even if he or she saves the day somehow, preserving a human life or an architectural marvel, that victory is ephemeral. The Oxford historians return home knowing that everyone they met on their journeys—people who were real and vividly alive just the day before—has lived out their mortal span.

I’ve heard Willis say more than once that time travel is an inherently sad genre, because the traveler moves through a world that is already gone. Even if he or she saves the day somehow, preserving a human life or an architectural marvel, that victory is ephemeral. The Oxford historians return home knowing that everyone they met on their journeys—people who were real and vividly alive just the day before—has lived out their mortal span.

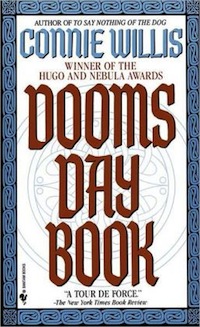

“Fire Watch” isn’t long, and when you’ve polished it off and are for more, I say jump right into Doomsday Book, the book that Jo Walton memorably calls “…the book where she got everything right.” This is a full-length novel, and the concept is exactly the same… but this time the young historian, Kivrin, is mistakenly sent to a time and place that makes surviving a Luftewaffe bombing seem about as hard as spending Thanksgiving with a mildly dysfunctional family.

The book is of academic interest, too, when set against “Fire Watch,” because Willis does more worldbuilding on that Oxford future, not to mention developing the time travel technology that lies at its heart. Oh, and if you’re keeping score? Doomsday Book isn’t one of the funny ones. It boasts, among other things, a truly impressive body count. Don’t blame the messenger, though; she’s just working with what history dished out.

What’s next? If you’d like a palate cleanser, here are a few more of the delightful stories you could dip into: “At the Rialto,” the politically sharp-edged “Ado” and “Even the Queen,” or perhaps her War of the Worlds Martians vs. Emily Dickinsen tie-in, “The Soul Selects Her Own Society” are especially great. Or, depending on when in the year you manage to get to this point, consider checking out the Christmas cheer in Miracle and Other Christmas Stories. (Mur Lafferty has written eloquently about that collection–go see!)

What’s next? If you’d like a palate cleanser, here are a few more of the delightful stories you could dip into: “At the Rialto,” the politically sharp-edged “Ado” and “Even the Queen,” or perhaps her War of the Worlds Martians vs. Emily Dickinsen tie-in, “The Soul Selects Her Own Society” are especially great. Or, depending on when in the year you manage to get to this point, consider checking out the Christmas cheer in Miracle and Other Christmas Stories. (Mur Lafferty has written eloquently about that collection–go see!)

Then, after you’ve caught your breath and dried your eyes, read the next time travel novel, To Say Nothing of the Dog, to see what happens when she takes the same universe and the characters you know (by now, quite well!) in a comic direction.

This essay is about getting to know the writing of Connie Willis from an imagined position of complete innocence. It’s so tempting for me to go on forever, poring through all the stories, trying to determine the most sparkly order for reading all of these incredible works. I want to figure out when a person should get to the rampaging sheep in Bellwether or grapple with the Titanic disaster and near-death experiences in the somewhat prickly Passage. Just because I haven’t mentioned Remake or “Last of the Winnebagos” or “A Letter from the Clearys” doesn’t mean I don’t love them.

At this point you should have a good idea though, of what I’m recommending you do: take the opportunity to read the heavy stuff and then the light, to go at the long books and then chase them with a few of the shorts.

At this point you should have a good idea though, of what I’m recommending you do: take the opportunity to read the heavy stuff and then the light, to go at the long books and then chase them with a few of the shorts.

So the last book I’m going to talk about, the one I think you should skip and then go back to, is Connie’s first: Lincoln’s Dreams.

Lincoln’s Dreams is a strange puzzle of a novel. It’s one of those things I reread often. Unlike a lot of Willis’s work, it is set in America, during an American war, and it has all the elements you will by this time have seen in abundance in her other works: a knowledgeable researcher in possession of not nearly enough information, missed messages, misunderstandings, and big problem in the form of a doctor who thinks he knows it all, when he’s really just blustering to cover his own incompetence. It’s the story of a woman, Annie, who is having strangely believable dreams about the US Civil War, and a guy, Jeff, who she asks to explain them. Are the dreams paranormal in origin or merely a side effect of prescription drugs? We never find out.

It’s interesting to go back to this first novel after having read some of Willis’ bravura later work, to see where she started and how strong a writer she already was. Like Doomsday Book, Lincoln’s Dreams is filled with death and tragedy. But where Doomsday Book is about plague, Lincoln’s Dreams is her first major attempt to grapple, close up, with the most human of the legendary four horsemen: war. The dead of this first novel are not the unfortunate victims of microorganisms. They’re not even the anonymous victims of aerial bombing. They die by bombardment, bullet and bayonet, not to mention a thousand other calamities wrought by their fellow humans. Poor Annie is dreaming a nightmare that countless people lived and died through, and all Jeff can do is bear witness.

It is also a novel that defies just about every formula you could name.

Like a lot of books written before the era of Google and the smartphone, Lincoln’s Dreams has come to seem a little dated. Its plot turns, occasionally, on the idea of lost messages and it is packed with answering machines. Still, the one-way nature of the messages Jeff and Richard (the doctor) leave each other is echoed by the strange one-way pipeline Annie has to the 1860s. They are all shouting messages into a void without knowing if they’re doing any good.

Like a lot of books written before the era of Google and the smartphone, Lincoln’s Dreams has come to seem a little dated. Its plot turns, occasionally, on the idea of lost messages and it is packed with answering machines. Still, the one-way nature of the messages Jeff and Richard (the doctor) leave each other is echoed by the strange one-way pipeline Annie has to the 1860s. They are all shouting messages into a void without knowing if they’re doing any good.

This little bit of dating is another reason I think Lincoln’s Dreams isn’t the place to necessarily start with the novels of Connie Willis. It’s a book that reminds us that we too are the contemps of all her time travel stories. The present day world of Lincoln’s Dreams is already our past, one that some of us are too young to remember. The novel is tethered to a time that’s receding, day by day, as the present always does. This is both inevitable and something of an irony for a book which is about the past’s disastrous choices, and the indelible stamp they leave, decades and even centuries later, on the present.

A.M. Dellamonica has a book’s worth of fiction up here on Tor.com, including the time travel horror story “The Color of Paradox.” There’s also “The Ugly Woman of Castello di Putti,” the second of a series of stories called The Gales. Both this story and its predecessor, “Among the Silvering Herd,” are prequels to her Tor novel, Child of a Hidden Sea.

If sailing ships, pirates, magic and international intrigue aren’t your thing, though, her ‘baby werewolf has two mommies’ story, “The Cage,” made the Locus Recommended Reading List for 2010. Or check out her sexy novelette, “Wild Things,” a tie-in to the world of her award winning novel Indigo Springs and its sequel, Blue Magic.